This month’s elections for mayors and police and crime commissioners were contested under a revised voting system. In the first of a two-part blogpost, Alan Renwick examines how the shift affected the results. He finds that the impact was substantial, and that it specifically benefited the Conservatives.

The elections held earlier this month for mayors and police and crime commissioners (PCCs) took place under a revised voting system. The Elections Act 2022 abolished the previous Supplementary Vote (SV) system, under which voters could express first and second preferences, in favour of straightforward First Past the Post (FPTP). The changed rules were applied in four local mayoral elections last year. But this year’s local elections offered the new system its first large-scale outing: every part of England and Wales had either mayoral or PCC elections; a few had both.

So how did the new system fare? Did it affect the results? If so, whom did it benefit? This post endeavours to answer these questions, while a second part, which will be published tomorrow, will examine how the change affected the democratic quality of the elections in the round.

How the change affected the results

Ten combined authority mayoral elections and 37 PCC elections took place on 2 May. Under the new FPTP rules, Labour won nine of the mayoral contests, while the Conservatives won one. In the PCC contests, the Conservatives won 19, Labour 17, and Plaid Cymru one.

We cannot be sure what the results would have been had the former SV system still been in place, but we can make estimates grounded in evidence. To do so, it is easiest to break the contests down into three groups.

Group 1: majority victories

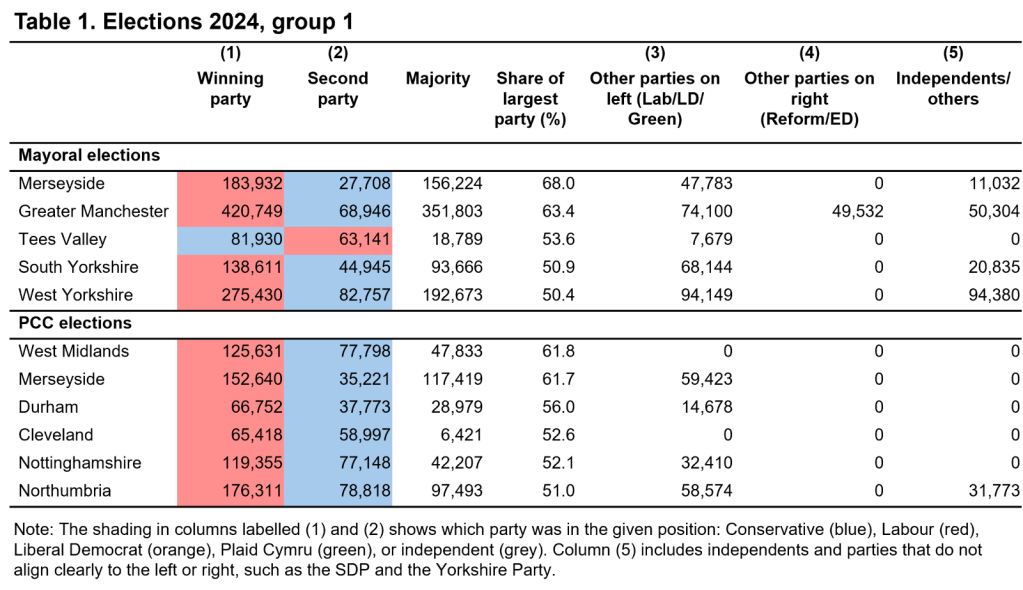

First were those elections where the winning candidate secured over 50% of the vote. Under SV, a candidate who exceeds 50% of first preferences is elected without turning to second preferences, so the FPTP and SV counts look identical. Of course, tactical voting pressures are different under the two systems, so we cannot be sure that a candidate receiving over 50% of votes under FPTP would also have received 50% of first preferences under SV. But a person who voted tactically for a candidate under FPTP would very likely give their second preference to the same candidate under SV. So it is safe to assume that, wherever the winner surpassed 50% of the vote under FPTP, they would also have won under SV. That applies to five of the 10 mayoral races and to six of the 37 PCC elections (Table 1). All but one of these contests were won by Labour.

Group 2: secure victories below 50%

Beyond these cases, we need to consider more carefully how voters would have used their second preferences under SV. In that system, if no candidate secures 50% of first preferences, all but the top two candidates are eliminated. In the second count, voters for the eliminated candidates then have their second preferences counted rather than their first. Whichever of the two remaining candidates has more votes once these are added is elected. So we need to predict where the second preferences of voters for eliminated candidates would flow.

We know from surveys and real elections that Labour, Liberal Democrat, Green, and Plaid Cymru voters are more likely to favour the other parties in this set than the Conservatives, while voters for Reform UK and other parties on the right (such as the English Democrats) are more likely to lean Conservative. Independents are mixed: some lean left or right; others are more ambiguous.

In the second group of elections, we can predict the outcomes under SV just on the basis of the direction of these flows. That is, assume that a higher proportion of second preferences of Labour, Lib Dem, Green, and Plaid voters would flow to whichever of these parties made it into the second count than to a candidate of the right. Similarly, assume that Reform and English Democrat voters would flow more to the Conservative candidate, and that voters for independents would split evenly. On these assumptions, the results this month would have been unchanged under SV in all of the remaining five mayoral elections and in 12 of the PCC elections (Table 2). Among these 17 races, 15 were won by parties on the left (Labour or, in one case, Plaid) with the Conservatives in second place. Because votes for minor candidates in the left bloc in these cases exceeded votes for minor candidates in the right bloc, the winner’s majority would, under the stated assumptions, have been greater under SV. Of the two remaining cases, the PCC election in Lincolnshire mirrored the same pattern on the right: the Conservatives led on first preferences; and there were more votes for minor candidates on the right than on the left. Finally, the North East mayoral election followed a different pattern, with Labour defeating the independent Jamie Driscoll. Driscoll being to the left of Labour, it appears unlikely that he would have been favoured by voters of parties towards the centre and right.

Group 3: potential switches

The third group of contests – the 19 remaining PCC elections – are trickiest. These are cases where, given the assumptions above, counting second preferences would at least have narrowed the FPTP victors’ majorities. To estimate whether the outcomes in these cases might actually have been reversed requires assumptions not only about the direction, but also about the magnitude of those flows of second preferences. Take, for example, the Warwickshire PCC election. The Conservatives defeated Labour by just 261 votes (out of 115,882), with a Lib Dem third on 24,867 votes. It seems certain that Lib Dem second preferences would have tilted sufficiently in Labour’s favour to have swung the result. But what of, say, Suffolk, where the Conservatives defeated Labour by 11,234 votes, and where the Lib Dems and Greens between them secured 37,029 votes? Would those votes have broken sufficiently for Labour to switch the winner?

Table 3 offers one way of addressing that question. It makes several more detailed assumptions: that 80% of voters would have cast a valid second preference for one of the remaining candidates; that voters for eliminated parties on the right (Reform UK and the English Democrats) would have split by a four-to-one margin for the Conservatives; and that voters for independent candidates would have split evenly. These assumptions are educated guesses, based on evidence from past elections and opinion polls. There would in reality have been much variation from case to case. But the assumptions allow us to explore further all the same. The final column in Table 3 then shows, given these assumptions, what proportion of voters for eliminated parties in the left bloc would have needed to break for the remaining party from that bloc rather than for the Conservative candidate in order for the Conservative to be defeated under SV.

The Derbyshire result is the odd one out in this table, as it is the only one where Labour led on first preferences. Had almost every Reform UK vote transferred to the Conservatives and very few Lib Dem votes gone to Labour, the Conservatives could have won on second preferences. Under the assumptions I have made, however, too few Reform votes would have transferred to the Conservatives to make up the gap, even if not a single Lib Dem vote went to Labour (as indicated by the 0 in the final column). While the reality might have been somewhat different, Labour would have hung on under any remotely plausible assumptions.

All the other contests in Table 3 were won under FPTP by the Conservatives. In Warwickshire, for example, given the assumptions, even a very marginal split of valid Lib Dem second preferences in favour of Labour over the Conservatives – by 50.7% to 49.3% – would have been sufficient to produce a Labour winner. In Suffolk, by contrast, 69.0% of Lib Dem and Green voters expressing an effective second preference would have been needed to give that preference to Labour rather than the Conservatives. To estimate how many of these results might have flipped under SV, we need a sense of what proportion of votes would really have transferred in this way.

Here, some comparisons with past elections are helpful. In Humberside in 2021, Lib Dem voters who expressed a second preference for one of the remaining candidates broke by a ratio of 55.0 to 45.0 for Labour over the Conservatives. By this standard, Warwickshire, Leicestershire, Thames Valley, and Gloucestershire would all have tipped from the Conservatives, and Cambridgeshire would have been on a knife edge. Alternatively, we might take the Leicestershire 2021 result – where Lib Dem effective second preferences leaned Labour by a ratio of 58.7 to 41.3 – as our point of reference. In that scenario, Wiltshire and Humberside would also have turned. Finally, using the pattern in the London 2021 mayoral election draws several more contests into play. Here, Lib Dems who expressed a preference for either the Labour or Conservative candidates split just over two to one for the former, potentially tipping the results in Staffordshire and Sussex to Labour. That London election had 20 candidates, so many second preferences went to eliminated candidates. With fewer candidates in the PCC contests, second preferences would have been more concentrated, perhaps shifting the outcomes in Hertfordshire, Suffolk, and Surrey too.

Summing up

The assumptions underlying these projections are, of course, contestable. Notably, there were significant independent candidates in several of these races who might have skewed strongly left or right, thereby complicating the picture. The bottom line is nevertheless clear: the shift in voting rules had a big impact. While it did not change the outcomes in any mayoral elections, it switched at least four PCC races, probably seven, and conceivably as many as 10 or 12. That is a remarkably large effect from a simple tweak to the rules.

Furthermore, because the left in British politics is currently more fragmented than the right, the switch from SV to FPTP favoured the Conservatives over Labour and other left or centre-left parties. By changing the voting system, the Conservatives significantly reduced their losses.

Was this a fix? That is, did the Conservatives alter the rules just to secure partisan advantage, or was there in fact a legitimate case that replacing SV with FPTP would enhance the democratic quality of these elections? That will be the subject of the second post in this series.

The second post in this series, examining the impact of the change in voting system on democracy, will be published tomorrow. Signing up as a blog subscriber via the box on the left hand side of the screen will enable you to receive the second post in your inbox the moment it is published.

About the author

Alan Renwick is Professor of Democratic Politics at UCL and Deputy Director of the Constitution Unit.

Featured image: Prime Minister Rishi Sunak and Mayor Ben Houchen (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) by The Conservative Party.

Pingback: The 2019 Conservative Party manifesto: were its pledges on the constitution delivered? | The Constitution Unit Blog

Pingback: The new voting system for mayors and PCCs: how it affects democracy | The Constitution Unit Blog