The UK is about to hold a July general election for the first time in almost 80 years. Sarah Birch, Erik Asplund, Maddie Harty and Ferran Martinez i Coma discuss why the risk posed by extreme heat could affect the conduct and outcome of the voting process.

It was a chilly start to the summer, and if this trend continues, a brisk walk to the polling station on 4 July could be a welcome means of warming up. But the mercury is slowing rising and a heatwave could be just around the corner. Many will have vivid recollections of sweltering in the 40-degree temperatures experienced in the UK for the first time in July 2022, resulting in a red alert for ‘extreme heat’ from the Met Office and ‘do not travel’ advice from Network Rail. Late July is historically the hottest time of the year, with the early part of the month not far off. The average high in July was 19 degrees a generation ago; it is now over 20 and rising, as shown in this Met Office graph:

The above image contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0.

So when Prime Minister Rishi Sunak called an election on 22 May, people may have wondered what was in store, especially as news was just coming out of temperatures nudging 50 degrees during polling in India, with dozens of poll workers dying as a result.

This is not the only recent election that has been hit by scorching weather. Campaigning in the US presidential election has recently been affected by heatwaves in the south-west, and unusually high temperatures shaped the June Mexican elections, the European Parliament election in Romania, the April election in the Maldives, last year’s snap parliamentary election in Spain, and the 2022 legislative elections in France, among others.

The El Niño phenomenon has been credited with bringing exceptionally high thermometer readings during recent polling in India, Mexico and the Maldives, though climate change has also been implicated in the unusual heat that many parts of the world have experienced this year.

The difficulties posed by hot-weather elections

Campaigning and voting in extreme heat can be problematic for candidates, party activists, voters, election staff, observers and journalists. Some will decide to stay at home; others will rise to the challenge but risk their health in doing so.

Around the globe, election specialists are now waking up to the dangers that heatwaves and other extreme weather events pose for elections. A project on the Impact of Natural Hazards on Elections by the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA), a Stockholm-based intergovernmental organisation, gathers evidence of these dangers in a dashboard of affected elections and a series of extended case studies. The project shows that elections can be severely affected by a wide range of natural phenomena. The willingness and ability of voters to cast their votes are common casualties of weather events, as are in-person campaign activities. In some cases, such events have also obstructed voter registration and polling; on occasion they have even led to unrest by frustrated voters.

Evidence of the impact of heatwaves on recent electoral processes indicates that they can have extremely detrimental impacts on wellbeing and orderly competition.

The high temperatures that have marred the presidential election campaign currently underway in the United States led to attendees at campaign events in Arizona and Nevada being hospitalised in early June, and the unusually hot weather spread to a greater number of states as the month wore on.

In India the deadly heatwave that swept across the country in the pre-monsoon season resulted in record-high temperatures, and even before polling was underway, campaigning was impacted with parties having to shift campaign efforts to early mornings/evenings. ‘It’s unbearable heat. It has become extremely difficult to campaign under a blazing sun,’ said Rabindra Narayan Behera, the Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) candidate for the Jajpur constituency in Odisha. As the electoral process continued, the heatwave claimed several lives. For example, at least 33 poll workers died in a single day in India’s most populous state of Uttar Pradesh. This also led to dissatisfaction amongst poll workers about the level of care provided by the Election Commission. The heatwave may have also had an impact on voter turnout. According to Defence Minister Ranjath Singh, the high temperatures were partly to blame for the low voter turnout in the first four phases in the election. Polling stations were reported to be unusually empty on the second last day of counting in Delhi.

In Mexico, there were record-breaking May temperatures in the run up to the 2 June general elections, with temperatures over 50 degrees in places. The heat caused several dozen deaths as well as power cuts. There were reported to have been waits of several hours in some of the special polling places intended for people who were travelling on election day, and at least one voter died after having fainted at a polling station.

The Maldives also experienced record-breaking temperatures at the time of its April elections, with ‘feels-like’ temperatures of 46.3 degrees. The heatwave occurred during the sacred month of Ramadan, which could have severely exacerbated health issues leading to heat exhaustion and heatstroke. The extreme heat likely impeded citizens’ ability to vote as residents were advised to avoid strenuous activities from 11 am to 3 pm, and the country saw a decrease in voter turnout of 8% in comparison to the last parliamentary elections.

The snap election of July 2023 in Spain took place during a heatwave that saw temperatures rise to over 44 degrees. As air conditioning is common in Spain, it was possible for political parties to relocate to indoor campaign venues to avoid the heat; they also shifted outdoor rallies to the morning hours.

How to mitigate the impact of hot weather on elections

Fortunately, there are a variety of strategies that can be used to mitigate the electoral risks of extreme weather. Contingency planning and coordination with other government agencies is hugely important in allowing electoral authorities to plan for elections. Simply keeping an eye on local weather forecasts can enable returning officers to prepare for possible heatwaves.

Then plans can be formulated for protecting electoral activities from the worst effects of heat. For example, in India, Mexico and Spain, cooling measures were undertaken in polling stations. India also put in place special provisions for at-home voting to enable elderly and disabled people to vote via mobile ballot boxes. The Maldives, for its part, extended the voting period for the parliamentary elections to enable voters to cast their ballots at a cooler time of day.

But the surest way of preventing an election from being disrupted by natural hazards is to avoid voting at times of the year when there is the greatest risk. Extreme weather tends to be seasonal; in the UK there is heat in the summer and storms in the autumn and winter. Some countries find that their election timing is constrained by constitutional provisions mandating fixed terms for elected office. Most parliamentary democracies are free to hold legislative elections at a time they choose.

The UK’s two most recent election date choices have been unfortunate from the point of view of natural hazards. The 2019 general election was held in December, following a spate of unusually heavy flooding, which research estimates boosted the Labour vote by approximately 2%. If temperatures remain on the cool side this year, the 2024 election date may not turn out to be a problem, but it was a risky choice, especially for a Conservative Prime Minister. Evidence indicates that hot weather tends to make people more attuned to the dangers of climate change, which is not a policy area on which the Conservatives are seen as strong. Moreover, the known health effects of extreme heat suggest that it is most likely to deter the core Conservative base of elderly voters from venturing out to the polling station.

In one sense this is reassuring, as it means that recent UK prime ministers have not been intentionally manipulating election timing for weather-related electoral gain. On the other hand, one would hope that with the growing danger of weather extremes, electoral events would be held at less risky points in the calendar.

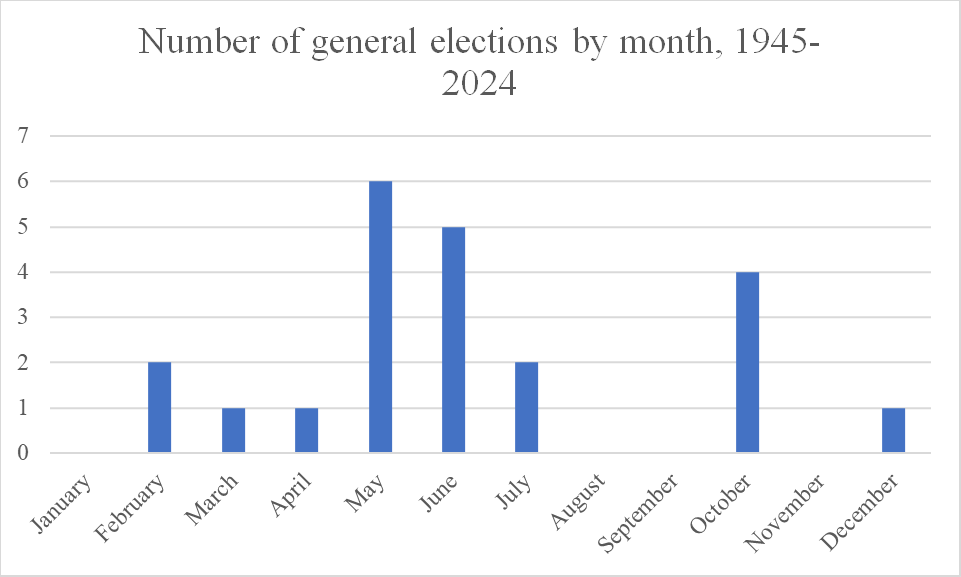

Generally speaking, this has been the case in the UK, as this graph shows:

Source: Table created by authors based on data from the UK Parliament.

The last time a UK general election was held in July was in 1945, shortly after Germany was defeated in the Second World War. More recently, the mild and generally dry period in the late spring and early summer has been a favourite time for governments to call general elections; in the nearly 50 years since October 1974, only three parliamentary polls have been held in months other than May or June: 1992 (April), 2019 (December) and 2024 (July).

Though the examples cited above indicate that measures can be put in place to protect elections from heatwaves, these cases also show that such measures are demanding as well as costly, and that they are never entirely successful.

The simplest and most expedient way of minimising the risk that electoral activities are impaired by heatwaves and other natural hazards would be for parliament to lock in a timing that has been practiced relatively consistently for the last half century and commit to holding elections in May or June. This might be accomplished, for example, by a variant on the now defunct Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011, which could specify a seasonal window for parliamentary elections, but not require the Prime Minister to commit to any given year (up to the five-year limit).

As the planet warms and the climate warps, many social processes will need to come to grips with unusual meteorological phenomena. Fortunately, the UK is well-positioned to prevent the worst of its ever-changing weather from disrupting elections, provided it does not call any more elections in July.

Disclaimer: Views expressed in this commentary are those of the authors, one of whom is a staff member of International IDEA. This commentary is independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed do not necessarily represent the institutional position of International IDEA, its Board of Advisers or its Council of Member States.

This is the latest in a series of posts on the 2024 general election. Sign up via the box in the left-hand sidebar to receive email notifications when a new post goes live. Additionally, the Unit’s annual conference will begin tomorrow. The conference will consist of four sessions, which will cover the topics that the Unit considers to be constitutional priorities for the next government: standards in government and parliament, House of Lords reform, the rule of law, and devolution within England. Sessions are accessible remotely and free to attend.

About the authors

Erik Asplund is a Senior Programme Officer in the Electoral Processes Programme, International IDEA. His research covers elections during emergencies and crises, risk management in elections, and training and professional development in electoral administration. Recent publications include Elections during Emergencies and Crisis: Lessons from Electoral Integrity from Covid-19 Pandemic.

Maddie Harty is an independent consultant. Her work includes contributions to the Impact of Natural Hazards on Elections, the Global Election Monitor, and trainings on electoral administration. Her MA in International Security from the Josef Korbel School of International Studies focuses on democracy and peacebuilding.

Sarah Birch is a professor of political science in the Department of Political Economy at King’s College London. She conducts research on electoral integrity and the political effects of climate change.

Ferran Martinez i Coma is Senior Lecturer in the School of Government and International Relations at Griffith University (Brisbane, Australia). He is an applied political scientist with consulting, public policy, research, and teaching experience. His research specializes on participation, electoral integrity, and electoral systems.