The main party manifestos have now been published, allowing exploration and comparison of their constitutional proposals. In this third post in a series on the manifestos, Alan Renwick looks at the parties’ policies towards elections and public participation. What are they promising, and what should we make of their proposals?

The rules of elections are far from settled. As a recent post on this blog set out, they have changed in numerous ways – both formal and informal – since the last general election in 2019. In their 2024 general election manifestos, all parties pledge at least some further reforms. Some also advocate additional forms of public participation in policy-making, such as referendums or citizens’ assemblies. But the policies on offer differ widely. This post outlines and assesses the proposals.

Votes at 16

Just one pledge in this area has hit the mainstream headlines in the course of the campaign so far, and that is Labour’s plan to introduce votes at 16. Keir Starmer highlighted this policy within a few days of the election announcement, and it is reiterated in Labour’s manifesto. It is matched by the Liberal Democrats, the Green Party, Plaid Cymru, and the SNP. By contrast, the Conservative manifesto says ‘We will not change the voting age from 18’. Indeed, the party has sought to weaponise the issue, claiming that Starmer’s policy is an attempt to ‘entrench his power’ for many years.

That Conservative riposte deserves to be greeted with decidedly raised eyebrows, coming as it does from the party that changed the voting system for mayors and police and crime commissioners in a way that benefited itself while damaging key democratic principles.

Still, young people tend to vote more to the left – and that association is exceptionally strong in the UK at present. It would therefore be surprising of self-interest was not part of Labour’s motivation. Furthermore, claims that fair representation demands votes at 16 are wide of the mark: there is in truth no conclusive principled argument for any specific age of enfranchisement.

On the other hand, the practical case for votes at 16 is strong. Voting is habit-forming: if you do it the first time you can, you are more likely to keep doing so. So democracy is enhanced by measures that boost voters’ participation in their first election. Yet giving people the vote at 18 is perhaps uniquely bad timing: with many people having just left formal education, or living away from home for the first time, they are outside the structures that might support participation. Being able to vote for the first time at 16 is much more propitious – as growing evidence shows.

But votes at 16 will have its full effect only if combined with high-quality, impartial citizenship education in schools. Sadly, not one of the manifestos mentions such education at all.

Registration, voting, and electoral administration

The Electoral Commission favours examination of options for automatic voter registration. The Liberal Democrats and SNP specifically endorse this, while Labour pledges, less precisely, to ‘improve voter registration’. Plaid makes a similar commitment, while other parties do not mention it.

A requirement for voters to show ID at polling stations was controversially introduced in Great Britain through the Elections Act 2022. The Conservatives say they will maintain this, and ‘change the law to ensure Veterans ID cards are valid identification in all future elections’. The Lib Dems, Greens, SNP, and Plaid would all scrap it. Labour would apparently keep it, but ‘address the inconsistencies’ in the system ‘that prevent legitimate voters from voting’. The Electoral Commission has long backed an ID requirement, so Labour’s position may be a reasonable compromise between competing considerations. But the devil would be in the detail of any reforms that the party brought forward if elected.

As I have argued on this blog before, the integrity of the electoral process has been undermined by provisions in the Elections Act 2022 allowing ministers to write a ‘strategy and policy statement’ for the Electoral Commission. The Lib Dems indicate they would reverse this, while the Greens appear to say that they would repeal the Elections Act entirely. Disappointingly, Labour’s manifesto does not mention the issue.

Indeed, there is a wider need to reaffirm government support for the role and independence of the Electoral Commission, to solidify the resourcing of electoral administration, and to modernise and consolidate electoral law. While such matters may be too technical for manifestos, they will badly need attention from any incoming administration.

Political parties and campaign finance

Public concern about the power of money in politics is – understandably – widespread. Past manifestos, notably in 2010, promised change, but nothing was done. Last year ministers controversially raised many donation and spending caps, in some cases by 80%, without consultation or debate.

The Liberal Democrats propose to ‘take big money out of politics by capping donations to political parties’; they would also work towards ‘radical real-time transparency’ for donations and spending. The Green Party, meanwhile, would ‘introduce a fair system of state funding for political parties to eliminate dependence on large private donations’, and also enhance the Electoral Commission’s powers to fine rule-breaking.

Labour would ‘protect democracy by strengthening the rules around donations to political parties’. Yet it appears by this to mean only that it would seek to inhibit foreign interference. If so, its lack of ambition in strengthening democracy is again disappointing.

One barrier to democratic participation is the cost of candidacy. The Green Party proposes ‘a permanent access to elected office fund to help with the costs of standing for election’, alongside measures such as job-sharing for MPs to enable greater access to under-represented groups. The Liberal Democrats would ‘requir[e] political parties to publish candidate diversity data’, as provided for the in Equality Act 2010. Again, other parties are silent.

The voting system

The voting system – the set of rules determining the nature of the votes that can be cast and how these are counted – lies at the heart of elections. The Conservatives say, ‘We remain committed to the First Past the Post system for elections, maintaining the direct link with the local voter’. Labour does not mention the issue and therefore presumably intends (notwithstanding a 2022 conference motion) likewise to maintain the status quo. By contrast, all the other parties – Lib Dems, Greens, SNP, Plaid, and Reform UK – advocate a proportional voting system, with the Lib Dems, SNP and Plaid reiterating their longstanding preference for Single Transferable Vote. Most of these parties say nothing about how this change might come about, while Reform pledges a referendum.

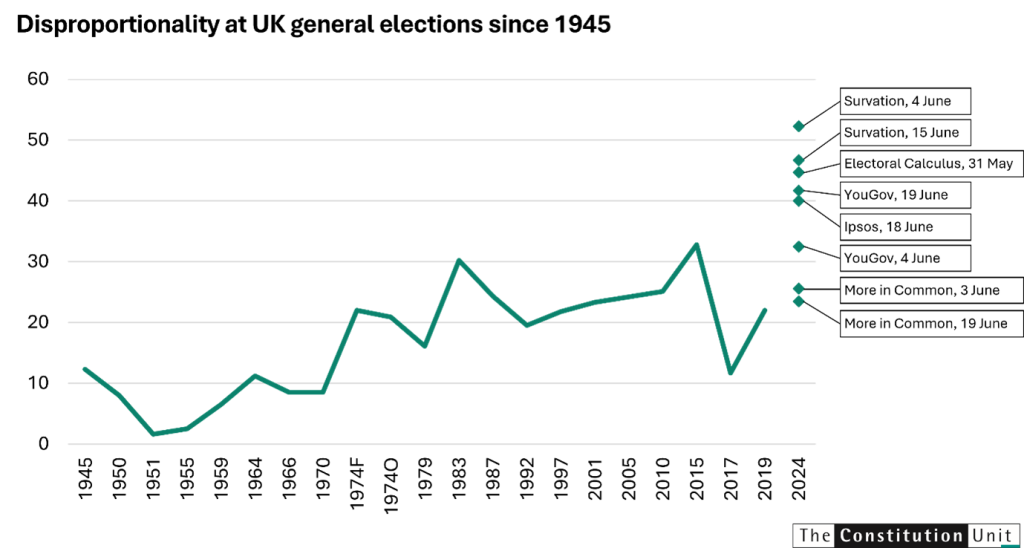

Given the likely election result, reform to the core of the voting system in the short term is thus improbable. Yet the longer-term future of First Past the Post may be less certain. The figure below shows levels of disproportionality in UK general election results since 1945, and then adds in the disproportionality implied by MRP seat projections published so far in the present campaign. Most of the MRPs suggest deviations between parties’ vote shares and their seat shares on an entirely unprecedented scale. In the most extreme case (Survation’s first MRP), Labour would win 77% of the seats on 43% of the votes, the Conservatives 11% of the seats on 24% of the votes.

Note: The figure uses the Sainte Laguë index of disproportionality, which I have argued elsewhere best captures the underlying meaning of proportionality. The overall pattern is the same if the more common Gallagher index is used.

The advantages of proportional systems in terms of fairer translation of votes into seats need always to be balanced against the benefits of majoritarian systems, which (typically) include clear lines of accountability. But an outcome such as this, if replicated on 4 July, would certainly advance the case for reform. If the current trend towards greater party system fragmentation continued post-election – as could well be imagined if Labour faced governing challenges and the Conservatives collapsed into post-defeat recriminations – even the main parties might reassess their support for the status quo.

Information and discourse during election campaigns

Several of the parties have policies designed to address concerns relating to disinformation in politics. The Green Party would ‘[a]mend the Online Safety Act to protect democracy, and prevent political debate from being manipulated by falsehoods, fakes and half-truths’. It also proposes support for ‘civic-minded local news publishers’. The Liberal Democrats advocate ‘a global convention or treaty to combat disinformation and electoral interference’ and ‘public awareness campaigns about emerging threats and misinformation campaigns online’; they would also ‘[s]upport the BBC both to provide impartial news and information, and to take a leading role in increasing media literacy and educating all generations in tackling the impact of fake news’. Plaid Cymru would ‘make it a criminal offence for elected politicians to knowingly mislead the public’. Labour’s manifesto again contains very little in this area. The Conservatives oppose further press regulation and say they would act to ensure the BBC upholds ‘diversity of thought, accuracy and impartiality as its guiding principles’. Reform UK strongly criticises the BBC and pledges to abolish the licence fee.

The Green and Lib Dem proposals in this area are worthy. Yet none of the parties appear to acknowledge the breadth of the challenge. As our research on public attitudes to democracy has shown, when people complain of politicians’ dishonesty, they have in mind not only outright lies, but also evasions and other attempts to mislead. Such discourse cannot be legislated away; but there is scant evidence from the manifestos or the campaigns that any of the parties are thinking about how to address these concerns.

Referendums, citizens’ assemblies, and other forms of participation

Public participation in decision-making can involve more than elections. Referendum proposals have been regular features in manifestos since 1997. This time, however, they are virtually expunged from the UK-wide parties’ thinking. The Conservatives, Labour, and the Liberal Democrats all affirm that they will hold no referendum on Scottish independence – while the SNP and Plaid want, respectively, the Scottish Parliament and Senedd to have the power to call a constitutional referendum. The only specific referendum pledge is that from Reform, mentioned above, on the voting system. The Conservatives would stop local councils from introducing 20mph speed limits or low traffic neighbourhoods without such votes. This switch away from referendums presumably reflects a realisation that they can all too easily become vectors of polarisation in which reasoned assessment of the options is squeezed out.

Recent years have seen much greater interest in more deliberative forms of public engagement in policy-making, such as citizens’ assemblies. Only the Liberal Democrats refer explicitly to such approaches, saying they would use ‘national and local citizens’ assemblies’ on issues such as ‘the climate emergency and the use of artificial intelligence and algorithms by the state’. As discussed in Meg Russell’s post on parliamentary reform proposals yesterday, Labour’s commitment to ‘seeking the input of the British public’ on proposals for Lords reform could also be fleshed out in the same way.

Conclusion

If a Labour government is elected, it will come to power committed to a modest programme of reforms on elections and participation: votes at 16; unspecified changes to voter registration and ID requirements; limits on foreign donations; perhaps a more participatory approach on some issues. These would all be sensible moves, but whether Labour has the ambition to make them well remains unclear. Other key matters – including on election administration, political finance, improving information and discourse, and deepening participation – are missing.

Public confidence in our democratic processes is at rock bottom. There is little in the manifestos to suggest our parties have grasped the extent of the need for change.

This is the third in a series of posts offering analysis of the parties’ manifestos, and the latest in a broader collection of posts on the 2024 general election. Sign up via the box in the left-hand sidebar to receive email notifications when a new post goes live.

About the author

Alan Renwick is Professor of Democratic Politics at UCL and Deputy Director of the Constitution Unit.

Featured image: Coventry City Council count, May 2016, (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) by Coventry City Council.

Pingback: Standards in the 2024 manifestos | The Constitution Unit Blog

Pingback: Parliamentary reform in the 2024 party manifestos | The Constitution Unit Blog