Boris Johnson’s long-awaited list of new peerage appointments was published today, and includes 36 names. Instantly, by appointing such a large number of new members to the Lords, Johnson has undone years of progress in trying to manage the size of the chamber down – returning it to over 800 members. Here, Meg Russell, a leading academic expert on the Lords and adviser to two different parliamentary committees on the chamber’s size, analyses the numbers – showing the detrimental effects on both the chamber’s overall membership and its party balance. She argues that Johnson’s new peerages make it clearer than ever that constraints must be placed on the Prime Minister’s power to appoint to the Lords.

Boris Johnson’s long-awaited list of new peerage appointments was published today, and includes 36 names. Instantly, by appointing such a large number of new members to the Lords, Johnson has undone years of progress in trying to manage the size of the chamber down – returning it to over 800 members. Here, Meg Russell, a leading academic expert on the Lords and adviser to two different parliamentary committees on the chamber’s size, analyses the numbers – showing the detrimental effects on both the chamber’s overall membership and its party balance. She argues that Johnson’s new peerages make it clearer than ever that constraints must be placed on the Prime Minister’s power to appoint to the Lords.

News reports about Boris Johnson’s first major round of Lords appointments have focused largely on personalities – the appointment of cricketer Ian Botham, the return to the fold of Conservative grandees such as Ken Clarke and Philip Hammond, who Johnson stripped of the party whip last year, and his reward of former Labour Brexiteers. But while some of these names may be notable, the bigger and more important issue is how Johnson’s new appointments will affect the Lords as a parliamentary chamber, and how they show up – yet again, and powerfully – the problems with the largely unregulated appointment process.

It is remarkable that in 2020 there are still no enforceable constraints on how many peers a Prime Minister can appoint to the second chamber of the UK legislature. Formally appointments are made by the Queen, but convention requires her to act on prime ministerial advice. The Prime Minister can choose when to appoint, how many to appoint, and what the party balance is among new members. A House of Lords Appointments Commission (HOLAC) was created in 2000, but has very limited power. It merely vets the Prime Minister’s proposed nominees for propriety (e.g. ensuring that their tax affairs are in order), and recommends an occasional handful of names for appointment as independent members. It can do nothing to police the numbers, or even the broader suitability of the PM’s own appointees. In theory, a Prime Minister could simply appoint hundreds of members of their own party (indeed, during the Brexit debates there were threats to do so both from the now Commons Leader Jacob Rees-Mogg and from Johnson himself). Appointees could even all be personal friends of the Prime Minister. The sole constraint is HOLAC’s propriety check (which is rumoured to have angered Johnson by weeding out some of his nominees) and any fear of media or public backlash. This unregulated patronage is one of the last vestiges of pure prime ministerial ‘prerogative’ power. Following last year’s Supreme Court case, even the previously unregulated power to prorogue parliament now exists within some legal constraints.

Aside from general concerns about patronage, there are two main interconnected problems caused by unregulated appointments on the House of Lords. First, the ever growing size of the chamber. Second, the lack of any rational basis for its party balance.

The size of the House of Lords has long been controversial. Significant political energy has recently gone into trying to contain, and to manage down, the chamber’s number of members – but Johnson’s appointments put that into reverse.

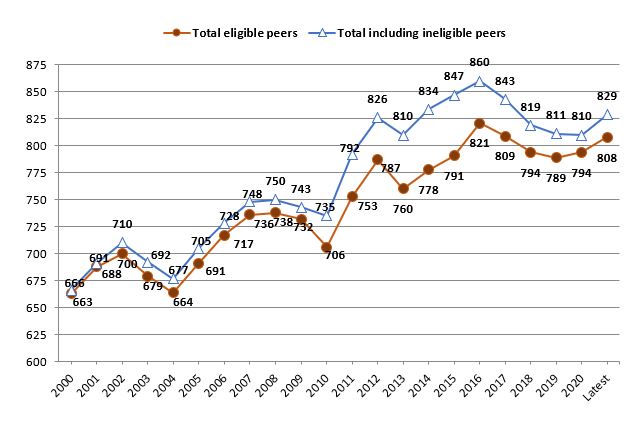

As the first graph shows, 20 years ago (shortly after the House of Lords Act 1999, which removed most hereditary peers) the chamber had just over 650 members – leaving it similar in size to the House of Commons. Subsequently, numbers crept up gradually under Prime Minister Tony Blair, who made 374 peerage appointments in just over 10 years (figures here, from the House of Lords Library). Since this outstripped the number of departures from the chamber (primarily resulting from deaths among older peers), its size gradually grew. The problem then accelerated significantly under Prime Minister Cameron, who appointed 245 new members in only six years. This quickly took the overall size of the Lords to well over 800 members. For contrast the second chambers in France, Italy and Germany respectively – whose first chambers are similar in size to the House of Commons – comprise 348, 320 and 69 members respectively. Famously the Chinese People’s Congress – arguably more of an annual conference than a parliament – is the only chamber in the world larger than the House of Lords.

Size of the House of Lords 2000 – 2020

Notes: All figures are from House of Lords Library/House of Lords Information Office. All except the most recent are for January of the relevant year. ‘Total including in eligible peers’ includes members on leave of absence or otherwise temporarily disqualified (who in principle could return).

Various people and groups raised the alarm about these developments. The Constitution Unit published two reports on the chamber’s growing size – in 2011 and 2015 – and the matter was debated regularly in the Lords itself, and considered by the House of Commons Political and Constitutional Reform Committee. In 2016 that committee’s successor, the Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee (PACAC), announced an inquiry into the size of the Lords (for which I served as specialist adviser). Later that year the matter was debated in the Lords, and a motion was agreed that ‘this House believes that its size should be reduced, and methods should be explored by which this could be achieved’. That vote led to creation of the Lord Speaker’s Committee on the Size of the House, chaired by Lord Burns (for which again I was an adviser), which reported in November 2017. The Burns committee set out a detailed plan to reduce the Lords’ size to 600, via a combination of retirements and voluntary constraints on the Prime Minister’s appointment power. It demanded, in the first instance, adherence to a ‘two out one in’ principle, so that the number of new peers should be just half the number departing, until the target size was reached. PACAC endorsed this broad approach in November 2018, but wanted both quicker and firmer action. This included a suggestion (recommendation 5) that the Cabinet Manual should set out new limits on the Prime Minister’s patronage powers.

As the graph above shows, there was a gradual slow decline in the size of the Lords over this period, from a high point in 2016, due to a combination of retirements, deaths, and the limited new appointments by Prime Minister Theresa May. May’s response to the Burns report was to pledge restraint, and she created just 43 life peers during her premiership – an annual rate around half that of David Cameron. Sadly, as the graph shows, this carefully-negotiated progress under May will be totally wiped out by Johnson’s 36 new appointments. Despite an early plea to the new Prime Minister from the Burns Committee, urging him to ‘take the same constructive approach to our work as his predecessor did’, no such commitment followed. By January, the Lord Speaker, former Conservative Cabinet minister Norman Fowler, was driven by rumours of the number of impending appointments to call for a complete moratorium, lamenting that ‘My chief hope had been that the Prime Minister would follow the course of his predecessor… I fear that my hopes may soon be dashed’. Sadly all of his hard work, and that of the Burns committee, will be undone by Johnson’s large round of new appointments.

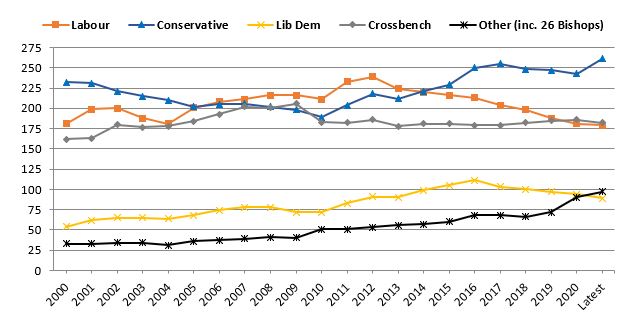

The second problem created by unregulated appointments is their relationship to the chamber’s party balance. A primary reason that prime ministers appoint to the Lords is to strengthen the position of their own party. A recurring problem over the history of the Lords is that incoming prime ministers often seek to rebalance against their predecessors’ appointments. But the Conservatives have been in government for 10 years, and became the largest party in the Lords in 2015 – as seen in the second graph. This also shows that Labour became the largest party in 2006 – a full nine years after coming to office – and stayed only fairly marginally ahead for the remainder of its term. In contrast the Conservatives were already well ahead of Labour before Johnson’s new appointments. These included 19 Conservatives and only 5 Labour. Over 10 years the number of Labour peers has declined from 211 to 179, while the number of Conservatives has grown from 189 to 261. A Labour lead of 22 when the party was last in office has now become a Conservative lead of 82. The Burns committee report, like various others mentioned above, strongly emphasised the need for balanced appointments according to a clear formula – in order to remove the long-running incentive for ‘tit for tat’ appointments. Johnson has very plainly flouted this principle, leaving Labour at a major disadvantage, and weakening parliamentary oversight powers as a result.

Balance of parties and groups in the House of Lords 2000 – 2020

Notes: All figures are from House of Lords Library/House of Lords Information Office. All except the most recent are for January of the relevant year.

So what is the solution? It cannot simply be higher numbers of retirements from the Lords. As Lord Fowler put it in January, ‘It is both unsustainable and unfair for peers to retire, only to find that they are immediately replaced by a Prime Minister who appoints more than the number who have departed’. As recognised by all the prior reports cited above, without constraints on the Prime Minister’s patronage there is no guaranteed means for the size of the chamber to be controlled.

We may now return to a battle of spin over who gets the blame for the chamber’s bloated size – the Prime Minister or the House of Lords itself. An oversized membership certainly damages the reputation of the Lords, and of parliament overall, as well as generating inefficiency, reduced effectiveness, and unnecessary public expense. None of this is good for the health of our democracy. But make no mistake, any such problem is wholly of the Prime Minister’s making – the Lords, particularly under the recent leadership of Lord Fowler, has made huge efforts to contain the situation.

Parliamentarians and parliamentary committees must now urgently return to this matter, not least as there is already talk of a further round of Johnson appointments to come, which would worsen matters further still. Short term, some have suggested that frustration in the Lords could spark radical non-cooperation, through peers refusing to ‘introduce’ excessive new members. In April Conservative Lord Balfe suggested that introductions should be limited to the number set out in the Burns committee report. But this approach would be controversial and ultimately unsatisfactory.

Longer term, the Burns committee sought carefully to lay out a non-legislative solution, based on common understandings and restraint. Commitment to these principles should immediately be reiterated in the Lords, by key parliamentary committees, and by other party leaders. But sadly, in an environment where those at the heart of the government machine have become dismissive of constitutional convention and constraint, the only sure way to control the size of the Lords is to legislate to remove the Prime Minister’s unfettered power.

To mark the 25th anniversary of the Constitution Unit we have launched a special fundraising initiative, encouraging supporters to make donations incorporating the figures 2 and 5. If you value our work, and would like to contribute to its future continuation, please consider making a one-off or regular donation. Contributions are essential to supporting our public-facing work. Find out more on our donations page.

About the author

Professor Meg Russell is Director of the Constitution Unit, and a Senior Fellow at The UK in a Changing Europe (UKICE) studying ‘Brexit, Parliament and the Constitution’. She is author of The Contemporary House of Lords: Westminster Bicameralism Revived (Oxford University Press, 2013), and has served as specialist adviser to both the Lord Speaker’s Committee on the Size of the House, and the House of Commons Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee, both on inquiries into the size of the House of Lords.

Pingback: Reform: What is the point of the Lords? – British Politics at Queen's

Pingback: Why Labour should adopt a two-stage approach to House of Lords reform | The Constitution Unit Blog

Pingback: Boris Johnson and parliament: misunderstandings and structural weaknesses | The Constitution Unit Blog

Pingback: What’s the Difference Between a Duke and an Earl? – A&C Accounting And Tax Services – Top Quality Accounting, Bookkeeping, Payroll And Tax Services- Oakland, CA

Pingback: Hacked! – What's the Difference Between a Duke and an Earl? | Bwisit

Pingback: The Constitution Unit blog in 2020: the year in review | The Constitution Unit Blog

Pingback: Lords are a-leaping and Ladies are dancing | Kirsten de Keyser for London

Pingback: Reform the House of Lords

Pingback: Monitor 76: Democratic lockdown? | The Constitution Unit Blog

Pingback: Wikipedia Don’t Want You to Know About the UK Coup So Here’s the HTML – Dress rehersal rag

Pingback: Boris Johnson and parliament: an unhappy tale in 13 acts | The Constitution Unit Blog

Pingback: Political pay-offs in Lords appointments – need for constraint | East Devon Watch